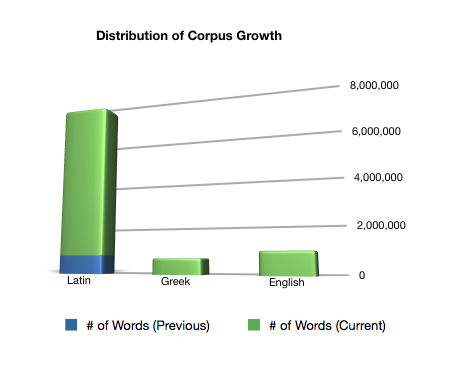

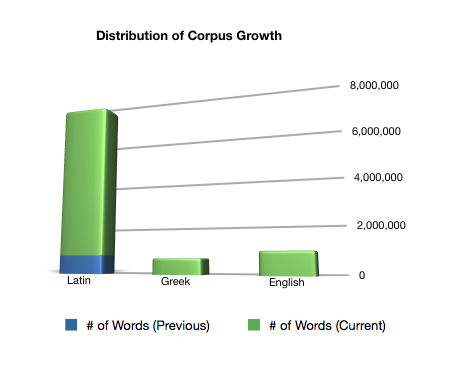

When the Tesserae tool is demonstrated to Classics researchers, the most frequently asked question by a wide margin is: “When can you add my text?” It’s a fair request, and a testament to the interest in computer-assisted investigation of intertextuality. Our answer to date has always been “we’re working on it.” This has not been a brush-off; in fact the rapid addition of new texts to our searchable corpus has been one of, if not the top priority of the 2012-2013 academic year. I am pleased to report that we have increased the size of our searchable corpus by a factor of 10, from approximately eight hundred thousand words at the beginning of the 2012-2013 academic year to over eight million words at the time of this writing.

Before I launch into a detailed account of our progress, there are two things I want to make clear:

- There are other development teams on the Tesserae project which never stopped growing the functionality of the system while my team worked to expand its reach. The results can be seen in (among other things) the new multi-text search, and the much, much faster back-end we now enjoy.

- The massive increase in the Tesserae corpus is the result of a team effort. Veterans of our scoring team returned and were joined by fresh faces who contributed to a deep talent-pool as attested on our personnel page. We were also given a much-needed boost by Chris Forstall, as I will explain.

Our goals for the year included the incorporation of the entirety of the Perseus classical corpus into Tesserae and the addition of important work in the English language. In order to add the texts from the Perseus database, it was crucial to preserve the hierarchy of text, book, and line-number with which the works were already annotated. Tesserae makes use of these markers and to strip the information out would be a waste. Yet there were several obstacles.

First, Perseus texts were added and annotated by many different researchers over a period of several years. Each text presented unique problems to its annotator. Where these problems repeat themselves, a single annotator might solve them the same way each time–but different annotators developed unique solutions. This complicated Chris Forstall’s task of creating a universal parser for the Perseus XML.

In addition, some of the variation in the XML-structure of the annotated texts is a natural result of differential structure of the works themselves. Plays are not organized like novels which are not organized like histories. The variety of structures is hinted at in Chris Forstall’s blog post. What is worse, several authors have been overly complicated by their textual tradition. Take Cicero, for example.

At one point, Cicero’s works were organized by text and chapter. These chapter numbers were based on the page numbers of a very early print publication, and they often break up the text mid-sentence. Later tradition re-divided the work into text, book, chapter, and line–often interrupting the old divisions. Modern texts still include the old chapter numbers as well as the new. The researchers at Perseus, in their effort to faithfully reproduce the information contained in a print volume, include both numbering systems simultaneously in the XML structure of the text. Untangling these conflicting annotations correctly is time-consuming; luckily we were able to rely on the wise counsel of John Dugan and the tireless efforts of Anna Glenn in order to incorporate every single text in Cicero’s oeuvre into Tesserae. For those who aren’t aware, that’s a good chunk of Latin. Cicero’s works contain nearly half of the words in the existing canon of classical Latin.

In fact, the project was able to dramatically increase the size of the corpus in all aspects. Some numbers:

| # of words in the Tesserae corpus circa August, 2012: |

795,141 |

| # of words in the Tesserae corpus circa June, 2013: |

8,198,402 |

That’s an increase of 1,031%. It was made possible by the initial work of Chris Forstall, who developed a universal XML-parsing tool for use on the Perseus corpus, and the sustained efforts of our force of volunteers.

The increase has been so dramatic that we are currently considering new methods of organization to relieve the now-overburdened menu system. In addition, still more texts are being processed even as I write, so if you’d like to make sure your particular text will be incorporated into the corpus, feel free to drop us a line, and be assured: we’re working on it.